|

I've mentioned before how my office is also home to the Makerspace carts, which include one of my favorite little bots...Ozobots! These bots can be used to visually code, and we love using them during reading! Whether it is story retell, sight word practice, or letter ID, students love using the Ozobots to practice their reading skills!

Ozobots are easy to use and highly engaging! To use with storytelling, you can either have pre-made mats with graphics already placed, or you can have students identify story elements they want to draw. Next, students will identify what Ozobot codes they want to use. If there's a repetitive part in the book, like "I'll huff and puff and I'll blow your house down," I have students pick one code to represent that saying. Then, you will have your students draw the path (solid black line) the Ozobot will travel. This path will sequence the events in the story. To add a bit more fun, you can add a photo from the story to the Ozobot (see the Twitter video above) and students can retell the story from the perspective of that character! Notes: -If your students make a mistake, you can cut a white Avery mailing/file label to size, cover the error, and redo the path. -If your students struggle at first to make the codes, you can print them on Avery mailing/file labels and students can these as sticker codes.

Ozobots can be used with other subjects as well, so feel free to get creative! If you'd like any of the resources or support with anything discussed in this post, let me know!

0 Comments

Today, I had a blast co-teaching a story retell lesson in first grade! As you may know, story retell, CCSS RL.2, is a skill kindergarten through third grade students work on each year. Teachers are always looking for new ways for students to practice retelling stories, and I was approached by a teacher to provide coaching support through co-teaching a technology integrated reading lesson. My office is full of Makerspace items, including Spheros, Ozobots, Ollies, but the cutest is definitely the BeeBots! We have Bluebots too, however for this activity, the teacher wanted to use the Beebots. For this lesson, students retold a familiar story: The Three Little Pigs. This was selected so students would become acquainted with coding the Beebot. I had pre-made cards representing different parts of the story, which students placed around the card mat. Next time, students will retell the story from their whole class reading lesson or small group reading book. Other lessons the teacher has brainstormed include placing sight words, math facts and number sentences, and science concepts like animal life cycles, under the cat mats.

If you haven't given Beebots a try, I highly suggest it! Students love coding, and teachers (and Instructional Coaches) love seeing another technology learning tool being used in the classroom! Every so often an interaction with a student provides invaluable perspective and outlook on both teaching and life. Today was one of those instances.

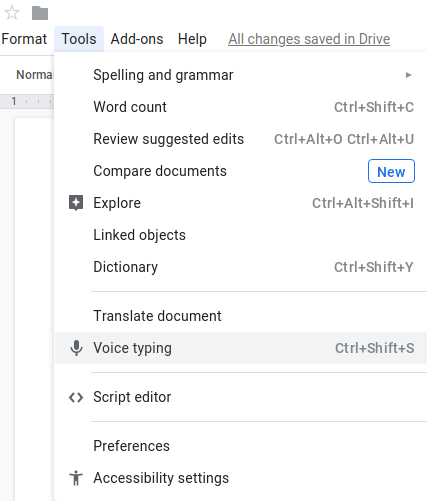

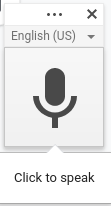

I was in charge of today’s PBIS (Positive Behavior Interventions and Support) Assembly, where we recognize students who have shown the RAMS Way (Respect, Always Responsible, Manners, and Safety) over the past month. Students receive awards, VIP tickets, play games, and are reminded to show the RAMS Way everyday, both in and out of school. Since it is almost Halloween, I chose to do a Halloween themed “Eyeball relay race” which involved students using a spoon to carry a bouncy ball eyeball (I found them at Target!) around a series of cones. For the younger grades they just walked/ran around the cones, and the older grades we had them use scooters. It was prior to the older grades’ assembly that the perspective I mentioned earlier was experienced. You see, while drawing names for students to participate in the game, I drew the name of a student who happened to be on crutches. For a second I thought I should draw another name to replace the student, however at just that moment the student in question walked by. I asked them to stop by the table where I was drawing names, and let them know I had drawn their name for the game, explained what the game entailed, and asked if there was a classmate they would like to pick to go in their place. Expecting to hear the name of one of their friends, I was surprised when the student said “No, I am going to do the relay.” A little perplexed, I asked if they were sure, and the student quickly replied, “Mrs. Laird, I still have one good leg!” and walked away. Believe me when I say I felt about an inch tall! In that one statement, “I still have one good leg,” I learned so much and was reminded how harmful it can be to have a deficit mindset. I need to remember to focus on what I do have, what I can control, and always have a positive outlook. This memory will stick with me for the rest of my teaching career and life, and perhaps I’ll find a way to turn it into a children’s story or weave it into a professional book! In my role as an Instructional Coach, I am frequently asked to support teachers in their work with students. Recently, an elementary student needed support with writing. This student had wonderful ideas to share, however classmates and the teacher were unable to decipher handwritten or typed stories. The classroom teacher knew there must be something to be done, and turned to me for support. Given the fact that we are a one-to-one technology device building, I have used Google’s speech-to-text tools (Voice Typing) before, and knew this would be a good place to start. A few days later, the student game to my office during writing time. After logging in to their Chromebook, the student opened a new Google Doc, clicked “tools” then “voice typing,” and their world opened! Immediately upon speaking and reading their rough draft aloud, the student paused the speech-to-text and looked at me with a grin on their face. “Mrs. Laird, do you know what this means?” the student asked. “My friends and my teacher will now be able to understand me and everyone will be able to read my stories!”

While Voice Tying isn’t new to me, and I have told other teachers about it, this was the first time I saw first hand a student see their world as a writer open up due to the tool. The next thirty minutes flew by as I watched the student become familiar with the intricacies of using Voice Typing, including remembering to say the type of punctuation, remember to pause periodically, and recognizing Google doesn’t automatically know how to spell the names of their friends. When it was time to go back to their classroom, the student told me how excited they were to take their writing notebook home over the weekend and type up other stories to share with friends. The thirty minutes I spent with this student reminded me the power technology has to open doors for students and allow them an outlet to share their voice, ideas, passions, and curiosity with the world.  For several years, Reciprocal Teaching has been one of my go-to strategies for reading. Over the past year I started using it in math instruction and am loving the results. In case you aren't familiar with Reciprocal Teaching, there are four strategies ("The Fab Four"): Predict, Question, Clarify, and Summarize. All four strategies are used within each lesson, and Reciprocal Teaching has an effect size of .74. Introducing the strategies can occur through read alouds (Lori has a great list in her book), or by using cards like the ones below. For more information, check out ASCD's Fab Four webpage, and Reciprocal Teaching at Work by Lori Oczkus. Through my Instructional Coach role, I have the opportunity to partner with teachers, and incorporating Reciprocal Teaching within reading and math is one of my favorite topics/goals. To support our work, I have created different resources related to Reciprocal Teaching, starting first with reading and later adding in math. Below, you can check out several of the resources I have created. I love the results I've seen from Reciprocal Teaching in reading and math, and cannot speak high enough of the strategies. If you would like support incorporating Reciprocal Teaching in your instruction, have questions, or would like copies of any resources, let me know.

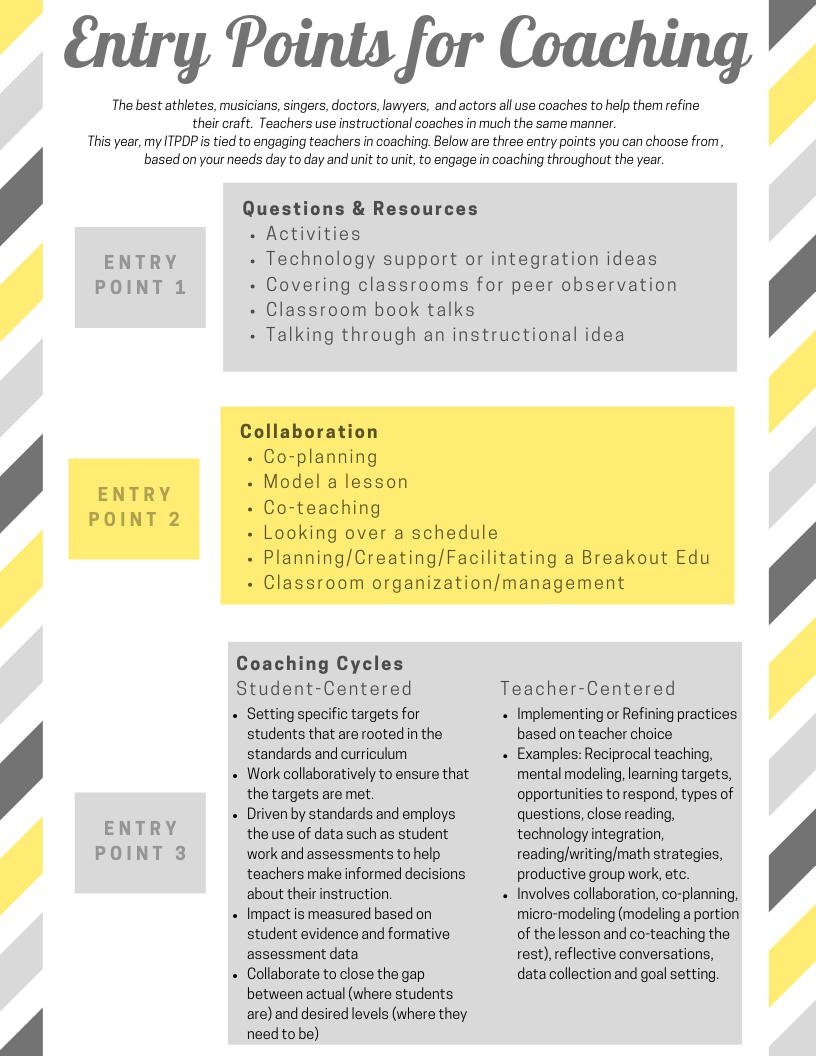

For this year's ITPDP (Individual Teacher Professional Development Plan), I decided to track the types and frequency of teacher engagement in coaching. To do this, I put together an "Entry Points for Coaching" graphic and shared it with teachers. Each trimester, I will track the three types of entry points, identifying trends and reflecting on changes I can make to my coaching work. In addition to allowing me to track engagement in coaching, the graphic also communicates coaching to the teachers I support. Is there anything you would add to the graphic?

If you would like a copy of the graphic, let me know. In my grad school classes, we are given the opportunity to reflect on articles and our own thinking. Below is an analytical essay from my Foundations of Inquiry course.

Article: Shulman, L. (1981). Disciplines of Inquiry in Education: An Overview. Educational Researcher, 10(6), 5-23. Prompt: In the conclusion to his essay, Shulman calls on educational researchers to not only engage in disciplined inquiry but to also participate as members of a community of scholars. He notes: "To engage in the process of inquiry, to become a scholar of and in education, is not only to take on the mantle of method and the rigor of discipline. It entails becoming an active member of a community of scholars and a community of educators. We must pursue and publish our research in ways that reflect the moral obligations of community membership. These obligations are entailed when we recognize that this is a community whose members are interdependent; each of us depends on the trust we can place in the work of other members of the community, because an intellectual and scholarly community rests on the assumptions that its member can build on each other's work" (p. 24) Starting from the premise that you think Shulman's argument is defensible, write a paper defending the ideal of disciplined inquiry and participating in the community of scholars against a possible objection. (For example: One might object that this ideal fails to account for the dissensus among scholars on norms of inquiry. What might a defender of Schulman say in response?). My Response: The “community of scholars” and the “community of educators,” to many these may represent or refer to two distinct groups, with little to no overlap in membership or purpose. Like generals vs. infantry, many scholars see themselves as research-focused, viewing education from a higher perspective without the desire to “get their feet wet”; while many teachers see themselves as learner-focused, viewing education from the front lines without the desire to “publish or perish.” I view them, as does Shulman, as “interdependent” members of a larger community (Shulman p. 26), who may have different processes or methods, but the same end goal: to teach. Certainly, the direct impact of student learning may be further removed from scholars, but the strategic information gained from this viewpoint allows for second-order changes to be implemented for learners across a system. And with teachers, the overall effect of the scholarly thought remains, albeit in a more subtle fashion, due to the cyclical nature (standards to be taught, practices to be employed, and the inquiry initiated to evaluate, and, if necessary, to adjust those instructional practices and standards) that is education, and pedagogy specifically. Recognizing the need for innovation in the way we teach, so that we can continue meeting the needs of students we serve, scholars and educators both engage in inquiry. This inquiry, as described by Dewey, involves both groups are testing for “scientific and social innovation” (Shulman p. 19). Without a doubt, just as there are different domains within education, there are also different methods of inquiry one can employ. For scholars, inquiry is disciplined, in that it is “framed by a question most important to the field” and utilizes defined “research settings, investigators, and methods” (Shulman p. 4). Inquiry is not a recipe or prescription for all scholars to follow; but, as with any scientific experiment, it needs to be repeatable. This requires communicating the precise actions taken, so that, if warranted, the experiment can be replicated. Also, given the communal aspect of scholarship, a single scholar’s word or findings should not be taken as law, but through reciprocal discourse, be examined to identify how the study’s learning can improve the field as a whole. Within the realm of classroom teachers, inquiry has a more problem-of-practice base, with educators identifying a learning objective, a student need, or an instructional practice that needs adjusting. Data, whether it be in the form of a pretest, common formative assessment, or peer comparison behavior data, will be collected, followed by an intervention (typically taken from scholarly research) being put in place, post-intervention data collected after a predetermined amount of time, and then analyzed to identify the impact of the intervention. Thus, on a smaller scale and with less-formal methods, the classroom teacher has modeled Lamert’s “teacher research” as they are the “subjects” and sometimes the “objects of research” and engaged in disciplined inquiry (Shulman p. 19). In my current role as an Instructional Coach, I serve as a bridge between teachers and scholars. It is in acting like that bridge, I am responsible for acting as a translator, of sorts, between the researchers and the teachers I serve. Based on the identified classroom needs, I seek out research studies, and based on the information the studies contain, model or co-teach in the classroom. In this way, I embody Shulman’s deeper analysis of the adage “publish or perish” as I rely on the “discoveries, integrations, and applications” that are published by scholars, and thereby learn from their teaching (Shulman p. 28). So, just as Shulman describes research as “beginning in wonder and curiosity, but ending in teaching” (Shulman p. 6), so too do teachers describe their learning. Given their focus on using inquiry both to innovate and to improve, scholars and teachers, together, leave their mark on the education system and students. With this in mind, these two communities aren’t so distinct after all. I LOVE reading, and summer is a great time to dive into learning. This summer I read several professional learning books, novels for book talks, and a textbook and articles for grad classes. After reflecting on all the titles I read, I narrowed down my list, and the top six are pictured above. Each book allowed me to grow as an educator and helped me gear up for another school year of supporting teaching and learning through Instructional Coaching.

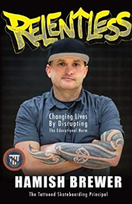

Looking forward to this school year, I already have a "to read" list started and will continue to share my learning here as well as on Twitter (@LairdLearning). What title(s) do you recommend I check out?  I recently finished Relentless by Hamish Brewer, and it was exactly the book I needed to read as I prepared to head back for another school year. Four themes that stood out to me as I read were:

I believe this is a must read for educators (teachers and principals) as it pushes and encourages you to look at your legacy and the steps you're taking to write your story.

As I gear up for the 2019-2020 school year, I can't help but think about 2020, not just as the beginning of another decade, but also in terms of 20/20 vision. When I hear 20/20 vision, a few words that come to mind are: clarity, distance, and screenings. School districts, leaders, and teachers have visions for their organization, it’s the "why" that drives their work and provides direction. This vision allows everyone to focus on what matters most - the students being served. Chances are your vision includes something related to students achieving at high levels, professional learning communities, or teacher collaboration, but how clear is your vision? Is it 20/20? Steps to Refining Your Vision Clarity: By clarity, I refer to having a clear understanding of where you and your organization are going. A professor I had in both my undergraduate and graduate programs frequently reminded us of the adage, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any path will lead you there.” This statement has guided my work and reminded me to pause and ensure my work, path, and end goals are aligned. An activity to try with staff tied to clarity and consensus is the One Word Challenge. Also, check out #oneword for examples and to connect with others. Distance: Are you on track to go the distance? Have you set goals, established an action plan, and implemented systems and structures (including personnel) to ensure success? To whom have you communicated your vision? Like teaching, leadership is a team sport, and as such you need a team who understand and are committed to the vision. Consider creating an infographic identifying your goals and post it around the building, school website, and on social media. The more eyes you have on your goals and vision, the more people there are to join in and support you on the journey. Screenings: What screenings, or checkpoints, do you have in place? How will you know when you’ve achieved your vision? Writing SMART goals, going on learning walks, utilizing Instructional Rounds, or using PLC protocols to discuss data can help inform your work throughout the year. Recognizing how quickly schedules fill up, push-notification services such as Calendar reminders or scheduled emails what can be a way to keep the screening frequencies at the forefront of your mind. No matter how your vision is phrased, if we truly want to make 2020 the best year of teaching and learning for our students, then we owe it to them to have 20/20 (or better) vision. So again, I'll ask: What's your vision, and more importantly, is it 20/20?

|

Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed